| |||||||

| Museum shows how 2,000 years of history ended | |||||||

FOLLOWING the final immigration of the remnants of Iraqi Jewry to Israel in 1951, more than 2,000 years of history in Iraq came to a climatic close.

As attacks against Iraqi Jews continued unabated, a daring and heroic operation to bring the remaining Iraqi Jews to Israel was initiated. Between 1948 and 1951, more than 121,000 Jews had been smuggled out of Iraq in an operation named Ezra and Nehemia. Following the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, the Iraqi government had intensified its antisemitic and violent persecution of the Jews, making life intolerable for Iraq’s Jewish citizens. Many Jews were charged with fictitious crimes and, in many cases, jailed. Some Jews were even executed on trumped-up charges.

Jews were forbidden to engage in all aspects of banking. Jews were dismissed from organisations such as the railways, post offices and finance because the Iraqi regime said they might act treasonably against the Iraqi state. Jews working in Iraqi government departments were fired. Jews were not allowed to have import or export licenses. Jewish property and businesses were taken by the state. It was estimated that the value of property sequested by the state was in the region of £60 million. Although the Iraqi regime wanted all its Jewish citizens out of the country, it still made it difficult for the remaining Jews to leave. The 1967 Six-Day War resulted in the remaining Jews to suffer more humiliation at the hands of the regime. Now only 10,000 Jews remained in Iraq. In 1969, nine Jews were executed in public under the pretext of spying for Israel. Iraqis were encouraged to come to the square where the executions had taken place to view the bodies.

In 2013, it was estimated that just five Jews remained in Iraq. The contribution over more than 2,000 years by the Jews of the area of modern-day Iraq cannot be overstated. The Biblical history of the region, formerly encompassing the ancient area of Babylon, is an indelible part of Jewish history and culture. The Pumbedita Yeshiva was a centre of learning during the era of the Amoriam and Geonim sages. Founded in the latter part of the 3rd century CE, it was, together with the Sura Yeshiva, a centre of Jewish learning that was to last for about the next 800 years. The city of Pumbedita was previously settled by Jews for a long time before the academy’s establishment, since the days of the destruction of the Second Temple of Jerusalem in 66CE. Pumbedita was situated on the banks of the Bedita, a stream of the Euphrates, and thus it was named Pumbedita. The modern-day city of Fallujah now stands in its place. The Jews of Pumbedita became the centre of Jewish culture and scholarship. It was to last until the advent of the Islamic Arab period in the seventh century.

Babylon would therefore become the centre of Jewish religion and culture in exile. Many esteemed and influential Jewish scholars, dating back to Amoraim, all have their roots in Babylonian Jewry and culture. The Iraqi Jewish community formed a homogenous group, maintaining a communal identity, culture and Jewish traditions. The Jews in Iraq distinguished themselves by the way they spoke in their old Arabic dialect, Judaeo-Arabic, the way they dressed, observation of Jewish rituals, for example, Shabbat and holidays, and kashrut. Many of the Iraqi Jews who moved to Israel settled in the town of Or Yehuda, a small town some 10 kilometres south-east of Tel Aviv.

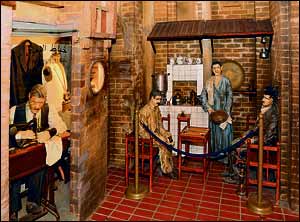

Together with six other founder members, the museum was opened to tell the story of the Jews in Iraq, up until the final aliya following the establishment of the State of Israel. The purpose-built museum was opened in 1988 by then-President Chaim Herzog. Apart from ritual objects donated by former Iraqi Jews from the world over, there were also archives. It became the largest centre in the world for documenting, researching, collecting and preserving the spiritual treasures of Babylonian Jewry. The museum displays dioramas of typical views, including inside a Jewish-owned home as well as a walk-through lane of Jewish owned shops that would have been seen in better times.

Recorded are the names and dates of young Jews who were imprisoned and murdered by the regimes. The museum also tells the story of the lives of Iraqi Jews after they came to Israel and had to live for some time in absorption camps and often under canvas. It was a hard life, but above all else they were free people in their own land.

If you have a story or an issue you want us to cover, let us know - in complete confidence - by contacting newsdesk@jewishtelegraph.com, 0161-741 2631 or via Facebook / Twitter

|