| |||

| Seaside resort was bought from Lebanese landowner | |||

FROM a geographical point of view Israel really is a very small country — so small in fact that to drive from the furthest point north to the furthest point south takes around six hours (probably longer for non-Israeli drivers).

However, in historical terms, the magnetic mosaic of sites and sights in Israel presents would-be visitors with tough choices as to what, where and how they will spend their time when visiting the country. One city somewhat off the tourist map is the northern coastal resort of Nahariya, the majority of tourists passing by the city entrance on their way to take the cable car down to the grottos in the white cliffs of Rosh Hanikra on the Lebanese border. This is usually after their having spent time beforehand visiting the Baha’i Temple and magnificent gardens in Haifa and the Old City of Acre, both UNESCO World Heritage Sites. What was once a small seaside town, periodically suffering shelling from Lebanon and terrorist attacks from the sea, present-day Nahariya is an attractive resort with magnificent beaches and a very attractive promenade. The central area of Nahariya boasts a plethora of small parks and sports more benches, pergolas and huge pots full of colourful flowers than one could imagine.

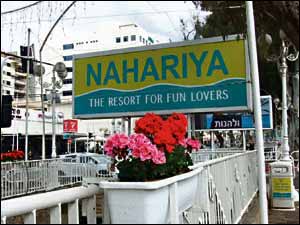

A huge banner stretched across one of the bridges states that ‘Nahariya is a resort for fun lovers’, and the banner certainly lives up to its promise. Local people are fiercely proud of their town. An elderly gentleman, resting on a bench in front of the skeleton of a multi-floor block of apartments under construction, gazes across the path and narrow road, over the river and towards a number of cranes. “I used to know almost everybody in Nahariya, but nowadays I only recognise a few of the people who walk by,” said Arieh, a former electrician, rather sadly. He perked up when adding that his children and grandchildren have almost all remained in the town. “When I was a young man, Haifa seemed so far away, but nowadays, with the railway, nowhere is far anymore,” he added. In the early 1930s, engineer Yosef Levi purchased the original tract of land that was to become Nahariya. The land was sold by a Lebanese landowner. Levi and a number of partners interested in developing the area founded a company, raised funds and acquired additional tracts of land and named the town in the making Nahariya because of the river — nahar in Hebrew being river.

A short drive along the rugged coastline toward the white cliffs of Rosh Hanikra and the Lebanese border in the near distance, sits an impressive sculpture, a memorial to those who sailed on the illegal immigration ships during the British Mandate period. Created by renowned environmental sculptor Yechiel Shemi, his art is a powerful reminder of those who risked their lives to sail the sometimes none-too-seaworthy vessels in order to bring desperate people to the shores of the land of their forefathers. Sitting on the rocks around the base of the sculpture, created from pieces of metal from those very immigrant ships, the sun goes gently down on the Mediterranean — a few fisherman becoming silhouettes against the calm waters.

|